Anti-choice advocates like to paint abortion seekers as follows: a selfish woman either accidentally gets pregnant or changes her mind about a pregnancy, waits too long to seek an abortion because she’s utterly careless, and then murders an “unborn” baby. Maybe the unplanned pregnancy is due to carelessness on her part, or rape, but that distinction doesn’t matter much. And she might change her mind because she loses her job and can’t support herself, or her relationship ends, or her relationship becomes abusive, or there is a fatal fetal abnormality, or her life is in greater danger than a “normal” pregnancy. These distinctions don’t matter, either. The fact remains that the woman is pregnant and decides not to be, and that is utterly unfathomable to them. Every new restriction we see is further proof of the fact that anti-choicers simply believe that women should be moms. As Jessica Valenti wrote in Abortion, Every Day:

“…for Republicans, banning abortion isn’t just about making abortion illegal—it’s about a return to traditional gender roles.” Abortion, Every Day, 2.21.24

After the Casey decision, lots of people said, “Well, I guess I’ll have to go to New York to get an abortion if I need one.” Except what if you so desperately need an abortion, you might die, and can’t physically travel to another state? Or, what if these “anti-trafficking” laws in anti-choice states make travel impossible anyway?

Or, more to the point, what if you aren’t in a financial position to leave your job or your kids for a couple days to go to another state for medical care? What if you’re Mayron Michelle Hollis, stuck in Tennessee, recovering from substance abuse, with a baby at home, trying to regain custody from the state of three other children, looking for stable work, supported intermittently by food stamps — and pregnant again? I need someone to tell me why Mayron could not get an abortion.

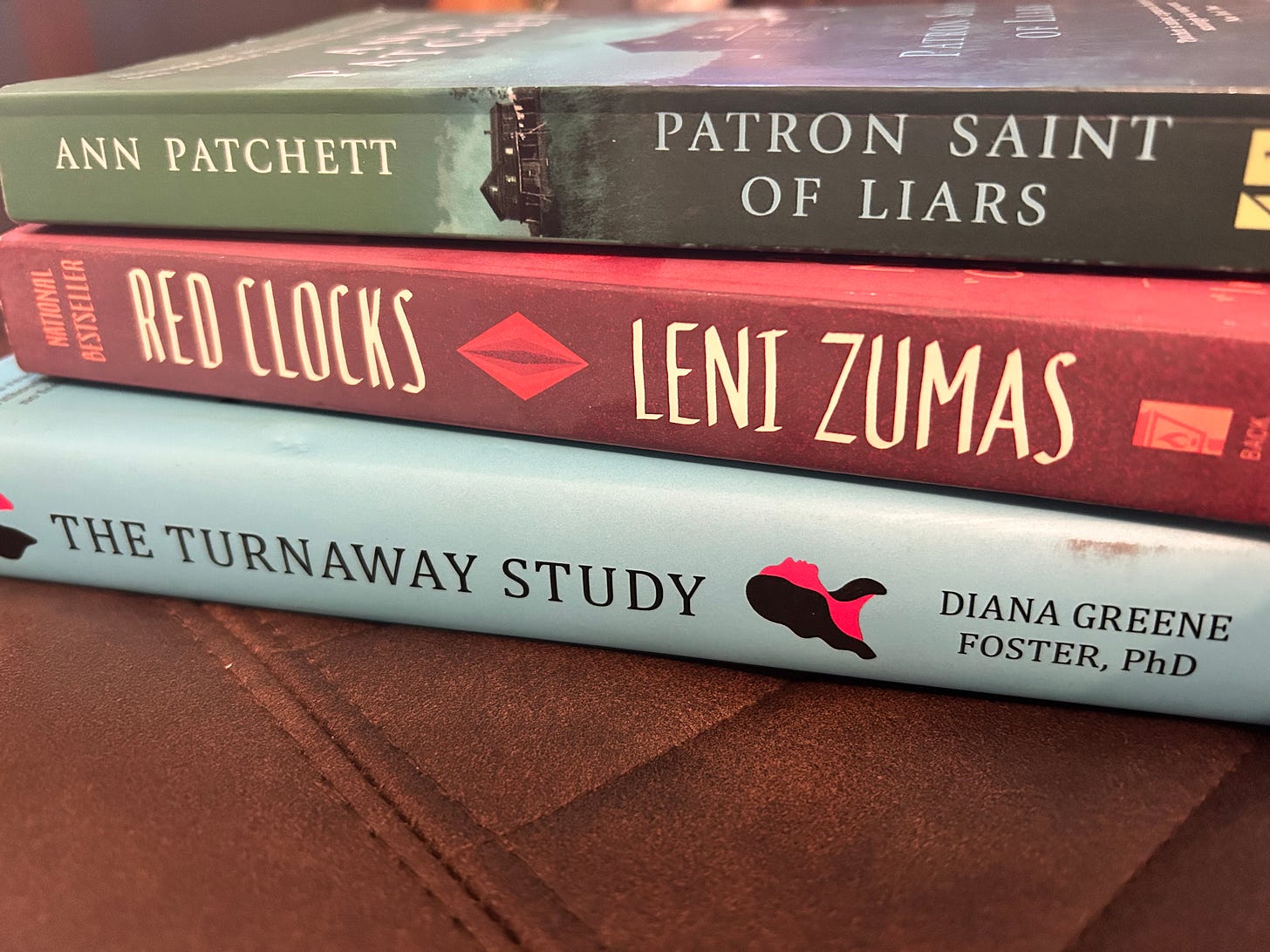

In 2020 Diana Greene Foster, PhD, published The Turnaway Study. Over ten years, she followed 1,000 women who sought abortions and either did or didn’t receive them for one reason or another, and tracked the outcomes.

Women make thoughtful, well-considered decisions about whether to have an abortion. When asked why they want to end a pregnancy, women give specific and personal reasons. And their fears are borne out in the experiences of women who carry unwanted pregnancies to term….[the study] brings powerful evidence about the ability of women to foresee consequences and make decisions that are best for their lives and families. — The Turnaway Study, p. 22

Women know what is best for their lives, for their families, for their future families. How can the same people who believe that all women have an innate instinct to do what’s best for families also believe that we can’t be trusted to make reproductive choices?

I know what cruel people might say — that Mayron shouldn’t have gotten pregnant again. Well, no kidding. I assume she thought the same thing when she found out she was pregnant. But how is that helpful? We are here now, and the answer Tennessee has settled on is to punish her, her new baby, and her existing children by forcing her to have another baby that she will struggle to care for.

I can’t stop thinking about Mayron and every person stuck in her position. How is she ever going to recover while carrying all of these burdens? How can she be forced to have more children when the state has already taken the ones she has? What is the state going to do to help her take care of her new baby? How can we not wonder if this is some kind of baby-making adoption scheme?

She is already facing every disadvantage I can imagine. We don’t know how she ended up here, and believing she is deserving in some way of all of it is repulsively patronizing and misguided. But that is exactly what I can imagine some conservatives arguing: that those disadvantages are the result of poor decisions, and we can’t reward poor decisions.

But Mayron is an adult. Adults don’t need to be rewarded or punished. We are not children or pets. Are we meant to think of adequate medical care and food stamps as “rewards” for being mothers?

If so, what kind of dystopian hellscape is this?

Well, it sounds very much like Leni Zumas’ Red Clocks.

I wrote my doctoral thesis on how fictional stories about mothers have evolved alongside reproductive rights in the U.S., and how particular novels have depicted abortion over the last 50-odd years. Red Clocks was published in 2018. It is a dystopian novel, set in the United States in roughly present day. Abortion is entirely outlawed, and, unfortunately for one of the characters in the novel who is trying desperately to get pregnant, IVF is next. You read that right: in this dystopian novel, published in 2018, the next bad thing on the horizon is an IVF ban.

I argued in my thesis that we need more novels like this, so that we can see the slippery slope before we start traveling it. I dedicated four years of my life to arguing that these stories matter, and that more importantly, the women making choices don’t owe us any explanations for their personal decisions.

But I’ve come to see the value in hearing those explanations. While I don’t think any of these women — Mayron and Kate Cox and Brittany Watts, to name a few brave souls — should ever have to share their reasons for their reproductive choices with us, it seems to be the only thing that makes people see that abortion access is not as simple as anti-choicers want us to believe.

But does it really make people see? Because Leni Zumas told us what would happen six years ago, and here we are today with an absurd Alabama Supreme Court decision that says that frozen embryos are babies, effectively ending IVF practices there, to say nothing of abortion.

The other book that comes to mind, of course, is The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood. And something she said upon publication of that novel has been playing on a loop in my brain for weeks: “It’s logical, you see, it’s logical” (Vogue, 176, no.1, 1986). In interviews about The Handmaid’s Tale, Atwood insisted it is not dystopian precisely because it is based in reality. She said everything that happened in her novel happened “somewhere at some time. I made nothing up” (Time, Sept 7, 2017).

One of the novels I used in my thesis doesn’t seem to fit the mold, but I included it because it precisely demonstrates that women don’t need to explain their choices. In Ann Patchett’s The Patron Saint of Liars [spoilers ahead], Rose runs off to a home for unwed mothers when she finds out she’s pregnant, leaving her husband with little explanation. While she ultimately keeps her daughter rather than giving her up for adoption, she ends up leaving her later. I love this novel because Rose doesn’t tell us why she left in any great detail — she just didn’t want to be a mother. Simple as that. Or so I thought. It was shocking to me how many Goodreads reviews expressed disbelief that someone would behave that way, or frustration that she didn’t better explain herself. Why do we think that we must understand the decisions of other people? That they must match our own? That they owe it to us?

I ask myself how we can be in this situation, now, in real life. But the answer was always there: “It’s logical, you see, it’s logical.”

Well said!