This episode is a bit different, which is why I’m calling it a bonus. It’s a much shorter interview, and it’s with an academic scholar, Dr. Katie Gaddini, who studies conservative Christian women and abortion rights. I hope you enjoy it.

Here’s why I wanted to speak to Katie.

Since I started this podcast, I’ve heard from lots of women who tell me they are struggling with their relationships with their mothers, or have cut off contact but are still suffering from the abuse they endured for their whole lives. Nobody has told me they cut off contact because of a political or religious disagreement.

Still, that’s what we tend to read about in the media, when they write about estrangement. And I’m sure there are plenty of examples of breaks occurring because of religion and politics. As conservatives become more entrenched with Trump and progressives despair over everything he does, the gulf between us widens. If that gulf exists in a family, it gets complicated.

And if that gulf exists in a family that lacks respect or consideration for any member, it might become the straw the broke the camel’s back.

Trump has said many times, and most recently in his joint session address, that he was saved by God from the assassination attempt last year, so he could “make America great again.” Plenty of his supporters have voiced the same opinion. These people believe, somehow, in spite of his poor treatment of many, many, many people, he is a good Christian.

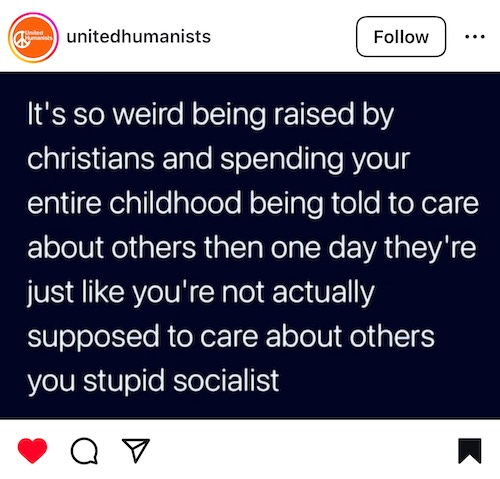

There’s a meme that makes me laugh every time I see it.

I think it’s something a lot of lefties who come from conservative households can relate to. We are told to help those less fortunate than ourselves, but when we vote for politicians who want to offer that support as part of our government, we’re called “stupid socialists.”

My bio says that I am from the Washington, D.C., area, which is true. It is the first place I remember living, and the last place I lived before moving to the UK. But for a good chunk in the middle, from about age 13-22, I lived in a small town in Pennsylvania. It was the kind of place where everyone goes to the high school football game on Friday, and church on Sunday. My parents took us to church occasionally before our time in Pennsylvania, but when we moved there with our mother following my parents’ divorce, my mom decided we would be dedicated Catholics. That is, my sisters and I would be. She didn’t go to church as consistently as we had to.

And I noticed, almost instantly, that I saw people in church who were not very nice to me in school. And there were a lot of people who were not very nice to me and my sisters, because we had a funny last name and we weren’t quite white enough to fit in. We had come from a pretty urban place where we saw many different cultures and races every day, and landed in a very white, Catholic, culturally-distinct place. My mother started buying homemade pasta from a woman who boxed it up in her house, I had to get my first holy communion at age 13 (I towered above all the kids), and even though I was told that a handful of the girls in my grade were my cousins, none of them acknowledged me.

And we were Republican. We were so Republican that I didn’t really even understand there was another political party until well into my teens. The Bill Clinton-Monica Lewinsky story was the worst thing that could have happened to America, according to the old men who lined the counter at the diner where I worked. That didn’t stop them from making jokes about my name, though.

And so I have always understood conservatism to be both a religious and a political ideology, and that they are often intertwined. This isn’t to say that I don’t know Catholics who are politically liberal, or atheists who are politically conservative. I love and respect many people of varying degrees of faith, and I think it’s an unfair characterization to say that all Christian conservatives want to take away women’s rights.

But we are seeing a lot of evidence of exactly that lately, in particular since the Right’s win in its long game against abortion rights. Abortion is now widely restricted – with many states pushing the boundaries even further. Some are proposing measures that make abortion murder punishable with the death penalty, and we’ve seen moves to actually restrict women’s movements. According to the brilliant Jessica Valenti who tracks abortion legislation in her newsletter, Abortion Every Day, “House Bill 609 [which has thankfully now been tabled] would criminalize anyone who leaves Montana to obtain an abortion that would be illegal within the state. An example: Montana only allows abortion after fetal ‘viability’ if the pregnant person’s life is at risk. That means if a woman learned at 26 weeks that her fetus had a fatal abnormality and got out-of-state care, she could be charged with ‘abortion trafficking’ for “transporting” her fetus across state lines.”

Abortion was embraced as a political wedge issue after Roe v Wade. In the late 70s, the so-called Moral Majority was founded by Baptist minister Jerry Falwell, harnessing the votes of Evangelical Christians.

Now, the SAVE Act, which would severely curtail the votes of married women across the country, can also be seen as a policy derived from religious practice. It’s a measure that claims to protect against illegal voting by non-citizens, but in practice it would make it very difficult and expensive for many women to vote, because they would need to present a birth certificate or passport with their legal name – which is tricky for many women who have taken their husband’s name. Sure, you can get a new passport, but that is time consuming and expensive.

Sarah Stankorb reported on this for The New Republic, pointing out that “A soft and effective way to suppress women’s votes has thrived in ultraconservative churches for years. Now, it has Christian nationalism as a vehicle and well-funded partners nudging another form of suppression through Congress.” Stankorb explains that in many conservative Christian households, it is understood that the man is in charge, that he tells the family how to vote, and that any wife who votes counter to his wishes is doing something very wrong. Stankorb writes, “Just as Christian nationalist ideals have seeped into our laws and discourse, ideals from its companion worldview, Christian patriarchy, have set the groundwork for women’s voter suppression through the church.”

I don’t have an interest in getting involved in the religion or politics or life choices of any woman, so long as she chooses them freely. That’s literally the entire premise of Bad Mothers.

But what concerns me is that politicians are again taking a personal, religion-based idea – like the belief that abortion is a moral wrong -- determining it to be useful politics for them, and engaging a religious group to vote for it to be the law for the entire country, essentially dictating the freedom and choices I have in my life.

With this in mind, it was wonderful to speak to Dr. Katie Gaddini. She is a Visiting Scholar at Stanford University, an Associate Professor of Sociology at the Social Research Institute, University College London (UCL) and a research associate at the University of Johannesburg, Department of Sociology. From 2022-2026 she is a United Kingdom Research & Innovation (UKRI) Research Fellow at Stanford University and UCL. Her debut book, The Struggle to Stay, was based on over four years of in-depth ethnographic research with single evangelical women in the US and the UK. She is currently writing a book on Christian women and conservative politics from 1970 to present. Her writing has been published in San Francisco Chronicle, The Conversation, The Hill, Religion & Politics, LA Review of Books, The Marginalia Review, and more. Katie holds master’s degrees from Boston College and the London School of Economics, and a PhD in Sociology from the University of Cambridge.

Share this post