As a kid, I read novels by Laurlene McDaniel compulsively. I don’t think she is very widely known, but she wrote YA books about young kids with terminal illness. It was very heavy stuff, and I remember reading late into the night and then sobbing in the bathroom, so as not to wake whichever sister I was sharing a room with at the time. As an adult I’ve often wondered what on earth drew me to these books, and also, why would anyone write about this for a young audience?

Clearly I like books that elicit an emotional response, but it’s sometimes too much. I couldn’t finish My Absolute Darling, for example. I still think — often — about the uneaten Swedish meatballs in Real Life. These are only fiction and still they were gutting.

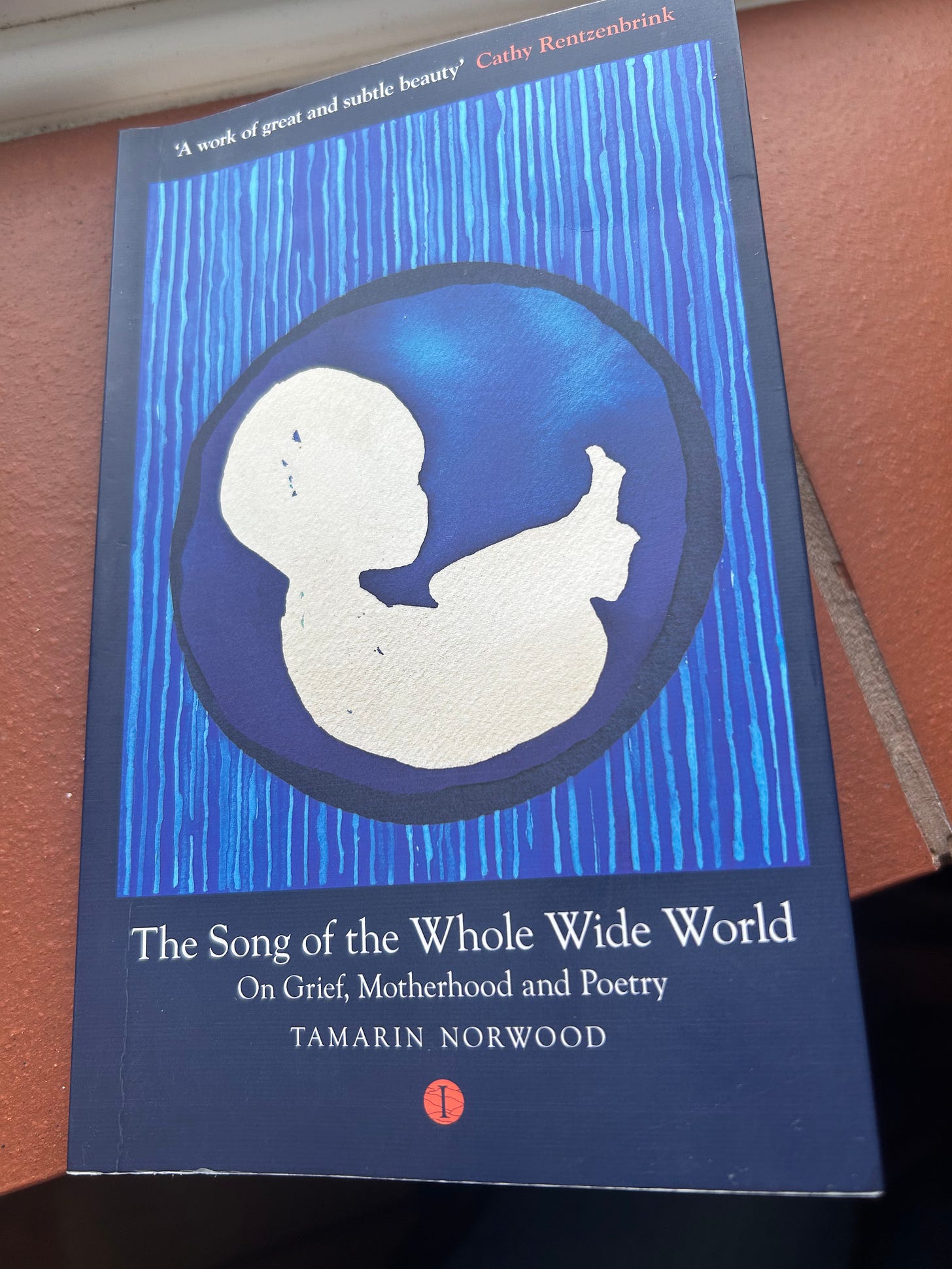

But The Song of the Whole Wide World is a memoir. While I know that most of those novels were likely borne of actual experience, the memoir is absolutely. And this one is devastating.

Tamarin Norwood writes about the death of her second child, Gabriel. In just 140 pages, she chronicles her pregnancy, his birth, his short life, and the grief that follows.

I had the pleasure of meeting the author at my local bookshop a few months ago, while she was on book tour and before I had the opportunity to read her book. And so I held back my most burning question: why did you continue a pregnancy when you knew the baby would not survive?

I didn’t ask because I was afraid my question would be perceived as a judgement. It’s hopefully stating the obvious, but I wouldn’t dream of telling anyone how or when to have or not have a child. The central thesis of Bad Mothers is to do what is best for you. Still, I wanted to know why she chose to suffer. I wanted to know the rationale. Perhaps I wanted to understand limitless desire for a child.

It turns out, though, that Tamarin addresses my question in Chapter 2, after the doctors tell her that the baby will not survive, but may live a short time.

“Nevertheless, between Gabriel’s birth and death, we could see a sliver of possibility. It was realistic to hope that he could crest into life and reach some peak of his own, whatever it was, and that this his furthest reach could be so rich and strange and so murkily remarkable to him that even if it was felt in distress it would still be something for him; still more and not less; it would still be life lived.” Page 23

I read this chapter several times, trying to understand, and in the end it makes sense to me. But the most important thing I took away from this experience was that it does not need to make sense to me.

The decision to have a child or an abortion is entirely personal, and the woman should never be required to explain herself. However, I am immensely grateful that Tamarin shared her deeply moving story, in her incredible prose. The story of Gabriel’s short life became one of the most impactful reading experiences of my life.

Shortly after finishing the book, for the very first time in my 41 years of life, I wondered if I might want a baby. I knew it was entirely down to this particular book, but why? Why a story about a woman who loses her baby minutes after his birth?

The only explanation I can fathom is that the compelling nature of Tamarin’s writing — I was right there with her for every word — wholly transferred her desire for this child’s life. My desire, it turns out, was fleeting. After a few days all consideration of motherhood passed.

But Tamarin wanted Gabriel for as long as she could have him, even if all of that time was shrouded in the knowledge that it would end very soon. She knew he was safe and comfortable in her womb, and she created a plan that would ensure he felt the same for as long as he lived following his birth. She was willing to suffer the grief that would inevitably follow the death of an actual baby in her arms.

And that was entirely her choice. While I can imagine many anti-choice activists would read this experience as evidence of a “good” mother who was willing to sacrifice herself for her unborn child, I see it differently. Perhaps she did sacrifice herself. But it was her decision to do so. She explains in the book that her doctors would also have supported a decision to end her pregnancy, and in some ways it seems they recommended or expected to terminate.

There are places in the world where this choice does not exist. What if Tamarin did not want to continue the pregnancy? What if she decided it was not what was best for her or her family? What if she had already sacrificed too much of her mental well-being to endure months of anxiety about what might happen in the course of her pregnancy? The pain that she suffers and describes so eloquently in this book would be unconscionable to force on a person. But it is something we are actually doing right now. Abortion restrictions mean that many women will be forced to endure the trauma of delivering a dead fetus rather than having the choice to end the pregnancy.

This is a beautiful memoir that does not get into the politics of choice. It is a pure story of a family grieving the loss of their child, flawlessly composed. But I do hope that it sheds a light why we must allow families to make the best possible choice for themselves.