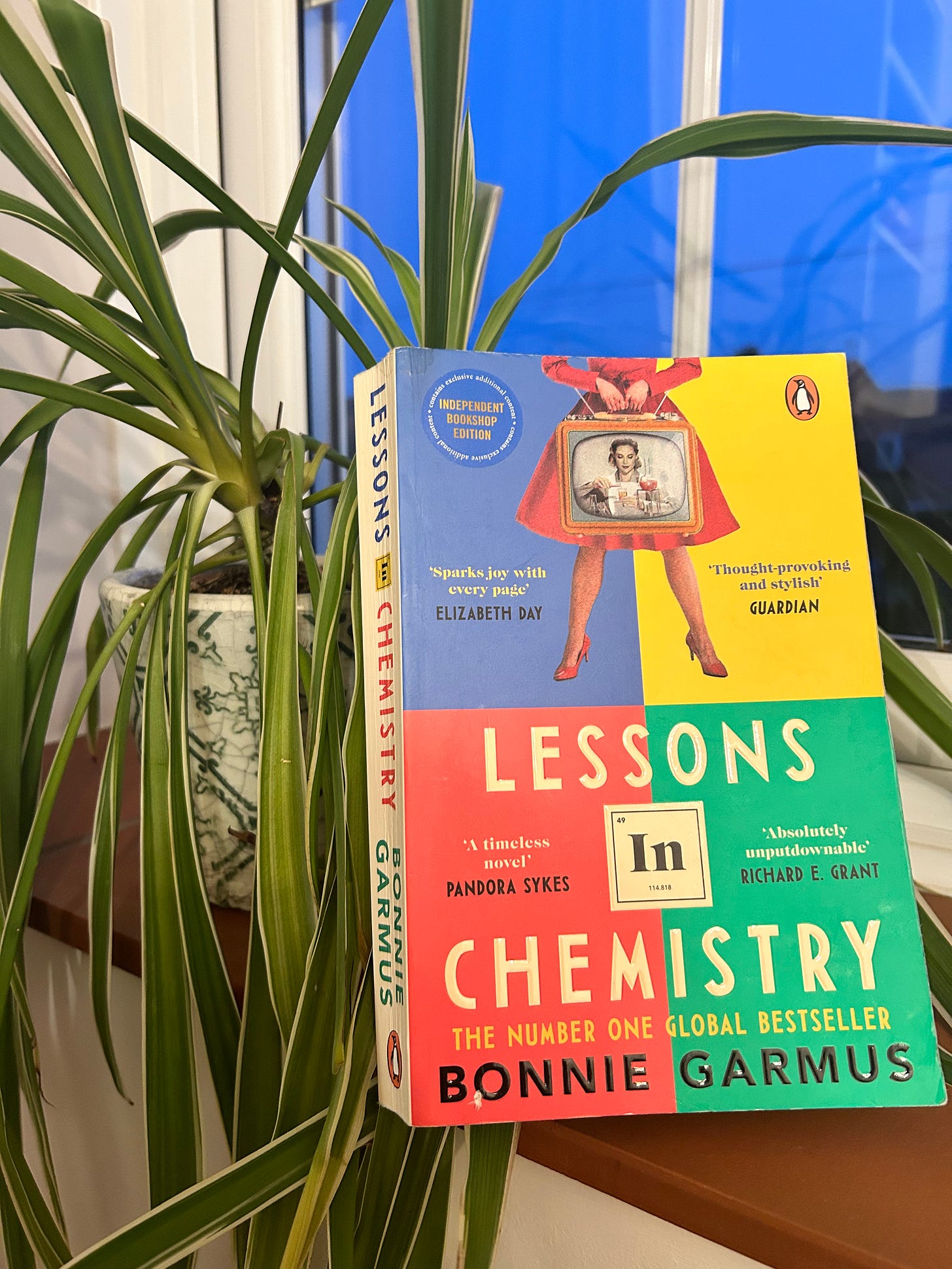

Bonnie Garmus' Lessons on the Patriarchy

On Lessons in Chemistry (Novel and Apple TV series)

Inside twenty pages of the novel Lessons in Chemistry, we learn that the heroine Elizabeth Zott’s grudges are “mainly reserved for a patriarchal society founded on the idea that women were less. Less capable. Less intelligent. Less inventive. A society that believed men went to work and did important things—discovered planets, developed products, created laws—and women stayed at home and raised children. She didn’t want children—she knew this about herself—but she also knew that plenty of other women did want children and a career. And what was wrong with that? Nothing. It was exactly what men got.”

And I imagine that women everywhere threw their fists in the air and cheered when they read that paragraph. I did. And then, like me, did they slowly realize that even as that passage is applicable to our lives now, the novel is set in the 1960s?

By far the most frustrating thing about studying women’s reproductive rights and all that goes along with that (and it’s basically everything to do with being a woman) is that there are constant reminders of how little has changed. Of course women can now do almost any job a man does without anyone batting an eye, but have we made it any more possible for women to work and have a family? Have we stopped judging women like Zott who express disinterest in having children or getting married?

No. And it’s disheartening to think of things that way. But as an avid reader and researcher, I feel confident that exposing this truth in books and on television will help us change this narrative in real life. Alan Sinfield wrote in 2004 that “[Literature] does disseminate, and with a distinctive authority, certain representations through the culture, inviting our assent that the world is thus or thus. It contributes, willy-nilly, to the making and legitimating of stories” (Literature, Politics, and Culture in Postwar Britain).

I worried that the television show would minimize Elizabeth’s desire to not have children, so I was relieved when Brie Larson said the words — that in addition to not wanting children, she didn’t want to be married. Elizabeth also confides in her doctor that she had hoped the pregnancy would end on its own — another provocative statement that also made its way into the series. What I found most interesting in both versions of this story was Elizabeth’s extraordinary love for her child — one she did not want but mothers exceptionally well. Of course it is possible to be an excellent mother, through hard work and dedication, without actually desiring that life for oneself. The problem is that those in the anti-choice movement seem to confuse ability with desire; they view stories like this as proof that we all should be mothers, when in fact we all should always have a choice.

One aspect of the television show that was noticeably different to the novel was the absence of unhelpful, judgemental women. In the novel, quite a few other women have real contempt for Elizabeth, but the show reshapes them into more helpful, if misguided, characters. This makes the TV Elizabeth into a bit of a superhero figure to admire rather than a character with which we empathize. I think both conceptions of this character can help advance a narrative of choice for women.

For those who have read the book and watched the show, of course the most dramatic change to the script has to do with Harriet, Elizabeth’s neighbor. In the book she’s a helpful older woman who gives parenting advice to Elizabeth and babysits a lot. On the show, Harriet is a Black community activist whose law career was put on hold because she had two children and her husband went to war. This storyline adds an important dramatic element to the show, showcasing the negative impact of white feminism on the feminist movement. Even our loveable Elizabeth becomes too wrapped up in her small victories to see the different and additional ways Harriet suffers because she is Black. Perhaps this additional plotline would have been too much in the novel, but I absolutely loved it on TV. The novel is a bit quirky, but Harriet’s more prominent role in the series added a level of seriousness that I think was lacking in the novel. That’s not to say I wouldn’t have loved more narration from 6:30! Read the book if you don’t get that reference ;-)

Stories like Zott’s (and Harriet’s) can help us begin to see the absurdity of sidelining women. And by “us” I mean politicians who vote against supportive family policies and uncles at Thanksgiving tables across America who ridicule Chelsea Handler for being pro-child-free. And maybe, someday, that will extend to the ill-informed harassers outside Planned Parenthood clinics. Maybe, someday, these people will see their discrimination for exactly what it is.

Tomson Highway Massey hall lecturer gave a great talk on our myths. I include the link here. He has a clear idea of where we went wrong. Also, watching the documentary film on John le Carre is very interesting. He talks about a childhood without a mother, and his noticing of the creation of enemies, lack of a real person in charge. He was the same age as my father so I watched so see how that generation saw things. Living in the aftermath of the war, reaching for success, factors that were pushed at that time. Distinct is the separation of family and work. To pull this together, I think you are correct that writing is very important because patterns emerge.

Last, in this random thought, on a return trip to Toronto from JFK, there were several men using their cell phones before the flight. One man, I overheard say, 'I'm not asking, I'm telling'. My father used this exact phrase. I was wondering, should I write about this? I ran into him in customs and said to him directly, that I had heard him say this, and that my father said this, and his father most likely said it, and even that maybe he could leave it out.

Later, I met a friend, a man whos father was perhaps a bit older, and he showed these same concepts, this kind of, ok, I have only a moment for you...my father was always this way (and more) so I think this emerging freedom we have to say no to rules that defy logic, and are backward, comes with understanding of whence they came! https://www.cbc.ca/radiointeractives/ideas/cbc-massey-lectures-tomson-highway/lecture-one-on-language I am a writer and myth and symbols are very interesting to me.