When I was a kid, my sisters and cousins would play a game we invented and called “Bad Mommy.” It wasn’t until this past Christmas, when we were reminiscing about our childhoods, that I drew the connection between this game and the title of my Substack.

“Bad Mommy” is a version of hide-and-seek, but with a storyline. One person is the Bad Mommy, and everyone else are her children. She puts us all to bed, tucks us in, reads us a story, and turns out the light. When she leaves the room, all the kids sneak out of bed. When Bad Mommy sees us, we run back to the bedroom, she follows and yells at us for not staying in bed.

Why did we call this game “Bad Mommy”? The mom is bad because she yells at us for getting out of bed. In my memory, when we try to sneak past the Bad Mommy, she’s sipping tea in the living room, or watching television, or cradling a doll that serves as her youngest child. So in our childish minds, the mom was “bad” because she wanted some time to herself, or to care for yet another child, and gets angry over being interrupted.

When I first moved to London I spent a long time puzzling together a way to make time for writing while also earning enough money to live while also paying tuition so I could keep my student visa and remain in the UK (it was not easy). I made a list of things I was unwilling to give up:

Live alone (no matter how small or which zone, no roommates)

Keep my indoor cycling gym membership

Reserve 15 hours of the work week for writing (enough to produce one new chapter of my novel each month)

Fly home at least 1x each year

The math was complicated, but I can’t help but pause over the indoor cycling. It doesn’t seem to fit very well, but I’d decided it was absolutely necessary to my happiness and well-being. Incidentally, I still believe this. I began exercising regularly in my early thirties, and quickly realized that it makes me feel more powerful and energized. But even more importantly, when the instructor is very good (shoutout to Jono at 1Rebel in London), I believe that if I can finish a class strong, I can also write and publish a book. I can take any number of rejection letters. I can keep trying. I can do anything.

It has been seven years and I managed to work out my finances well enough to live and keep that gym membership. I have moved out of London to the suburbs, and found a lovely indoor cycling studio. Most of the other people who attend are mothers, and there is usually some chit chat before class about when school holidays are or whose kid is playing this or that sport. But when class starts I like to think we are all the same — chasing after some strength and resilience and pride.

But I find it interesting that there are some exceptions. Some of the mothers will take calls during class, and one such mother always has a conversation along these lines:

“What is it? I’m in my cycling class…Well ask your father…I can’t talk now, it’ll have to wait…I need to go…bye…I said I need to go!…yes, fine, bye.”

This always makes me feel a bit annoyed — it interrupts my focus, but I also feel annoyed for her. I don’t know anything about this woman, but I can deduce that she has children old enough to use a phone and a husband at home with those children. And yet, she still feels compelled to answer when they call. She can’t even get 45 minutes to herself on a Sunday morning.

But does she need to answer the phone, or is she afraid of being labeled a Bad Mommy for carving out some time for herself?

A good mother, by my childhood standards and much of society’s, must be self-sacrificing and ever-patient. The difficulty and complications of being a parent are beginning to bend more toward reality and lived experience, but it is still generally believed that mothers should answer the phone. I wonder what it would take for this particular mother to let the phone ring? Or even better, to leave it in her bag during the class?

At the same time, these observations help me to remember the dramatic difference in lifestyle that I have created for myself. I don’t need to be reached by anyone. Nothing catastrophic will happen if there are a few hours during which I don’t look at my phone. My husband is an adult who can take care of himself. My sisters often have a lot to say to me, but I don’t play a role in their livelihoods and I live too far away to be any use in an emergency anyway.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

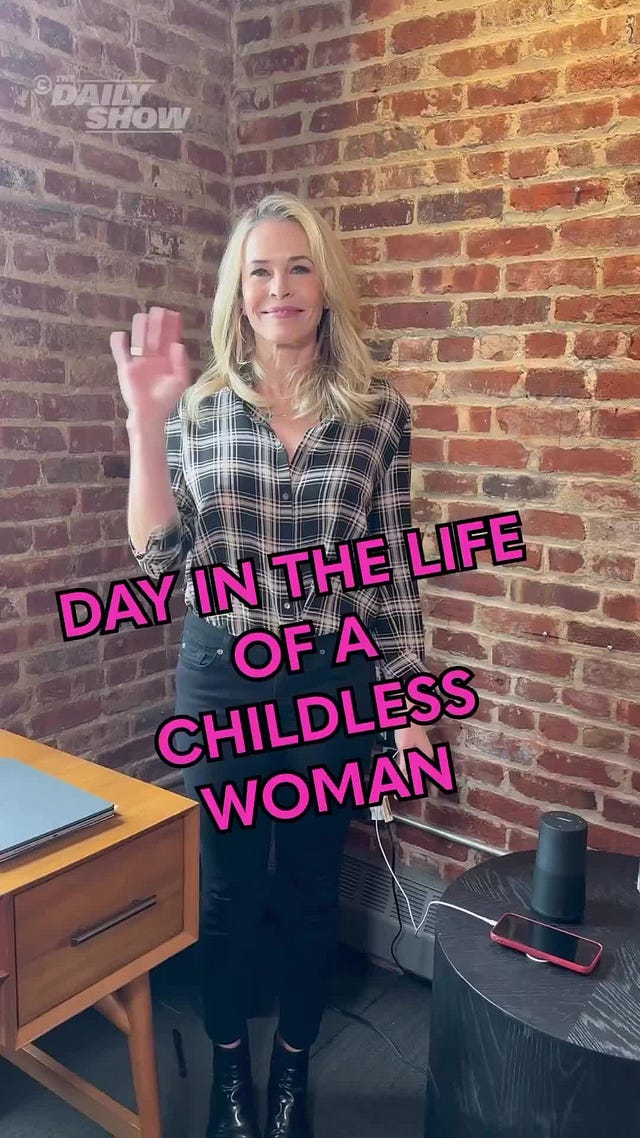

Chelsea Handler’s now-famous and semi-controversial video “A Day in the Life of a Childless Woman” centers mainly on free time and the ability to do whatever she wants. But shouldn’t there be time carved out for parents to do exactly the same, at least sometimes and without any guilt?

I have a few friends with children who seem to have nailed this lifestyle. They regularly take time away as a couple rather than as a family or leave the kids with in-laws for Saturday night. Of course, this requires resources. But it also requires an entirely new view of parenting — one that prioritizes the health and happiness of the parent and the couple.

Around the world, birth rates are plummeting and governments are clamoring for “incentives” to having children. The resources government can make available are important, but so is changing the narrative around what makes a “good” mother. A good mother can also have a career, a serious hobby, an active social life, or maybe just a valid and achieved desire for 45 uninterrupted minutes to herself every day. Of course, for some people there is no incentive to make parenting desirable, and that is a narrative that must be accepted as well.

When I look back on the “Bad Mommy” game, I can see that even as children we believed the mother deserved no time alone. We didn’t understand the value of that freedom because we were kids and nobody told us. In the game, the mother spends hours putting her kids to bed, over and over again, and is “bad” because she’s angry about it. Why didn’t we call it “Bad Kids” because we didn’t stay in bed?

I assume the game sprouted in our imaginations due to our own experiences, and my mother’s. Her children expected to be the center of her world, and if she resented that, she was “bad.” Perhaps children deserve to believe they are all-important. I wouldn’t dream of telling anyone how to parent their kids, but for those who would like children but worry about losing some freedom, their kids might be taught that parents are whole humans with other interests and obligations. Those things may always come second to the children, but they exist.

I loved reading this. It rang true all the way to the end. You’re a fabulous writer!

Excellent post, Monica!